What is the Border Adjustment Tax? Potential Benefits and Risks

With tax reform discussions likely to rise to the national forefront, this article provides analysis regarding border adjustment taxes and the recent House proposal. It assesses economic implications and historical comparisons to help you understand how you and your business might be impacted.

With tax reform discussions likely to rise to the national forefront, this article provides analysis regarding border adjustment taxes and the recent House proposal. It assesses economic implications and historical comparisons to help you understand how you and your business might be impacted.

Melissa Lin

Melissa has worked in ECM, tech startups, and management consulting, advising Fortune 500 companies across multiple sectors.

Expertise

More likely than not, you have recently found yourself barraged with headlines regarding the border adjustment tax (BAT), a portion of the Republican House Tax Reform Blueprint intended to overhaul the current U.S. corporate tax code. The proposal has emerged in response to common criticism that the current corporate tax rate of 35% and offshore tax deferrals create incentives for multinational companies to outsource jobs, make offshore investments, and take on unnecessary domestic debt.

While there would surely be winners, losers, and an estimated $1 trillion raised in revenue with the implementation of the proposed tax code, it is difficult to determine its exact implications without the actual legislative language, which has yet to be provided. With the nation coming off the heels of a failed healthcare reform attempt, the GOP will be making tax reform its top priority. Regardless of which side you sit on, you will want to understand the potential implications.

The BAT taxes imports, but not exports.

According to the nonpartisan Tax Foundation, a border-adjustment tax conforms to the “destination-based” principle whereby the tax is levied based on where the good is consumed (destination), instead of where it was produced (origin). Put simply, a BAT taxes imports but not exports, creating incentives for companies to import less and export more—a significant shift for the U.S. economy, which is heavily dependent on global supply chains.

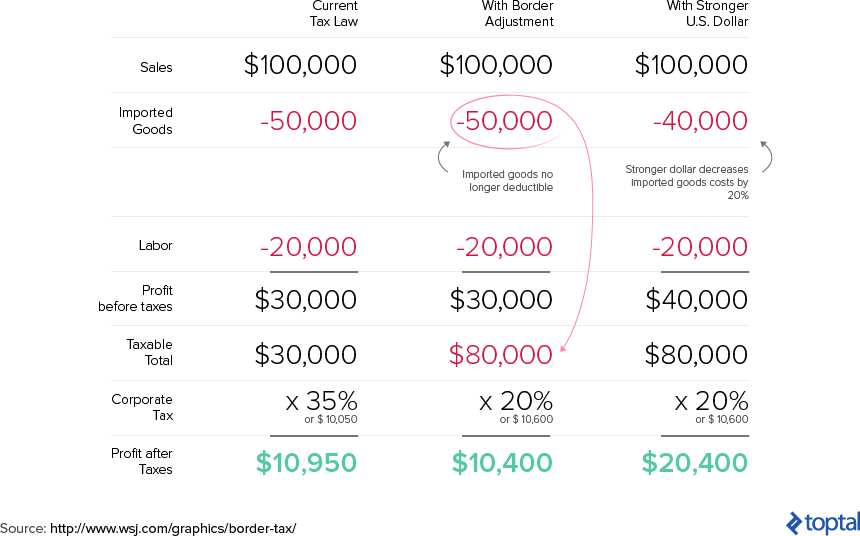

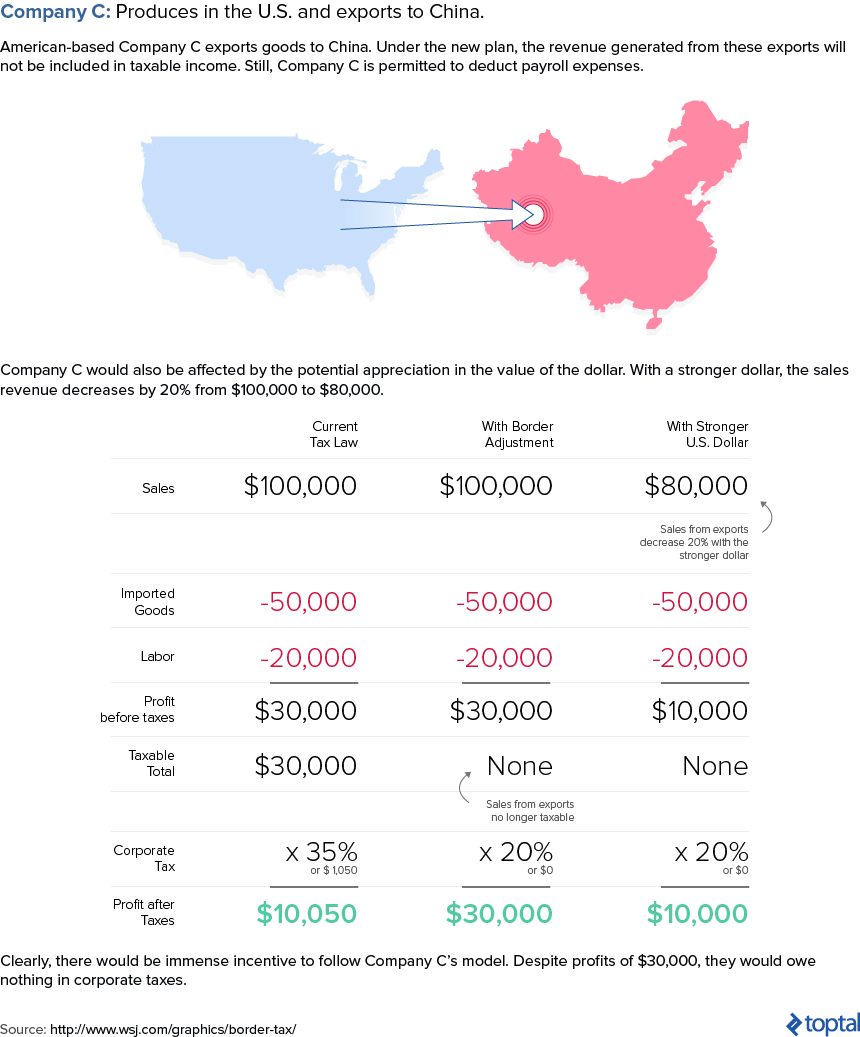

The House proposal applies a border adjustment to the U.S. corporate income tax. Per the plan, U.S. corporations would no longer be able to deduct the cost of purchases from abroad (imports) and would no longer be subject to taxes on revenue attributable to international sales (exports).

Despite common misconceptions, the border adjustment tax is neither a tariff nor a value-added tax. A tariff is a tax imposed only upon imports, and can be applied selectively to certain products, companies, or countries. In contrast, the border-adjustment tax in consideration would affect all imports and exports, and all countries.

In addition, the border adjustment tax is not a value-added tax (VAT), a taxation system widely adopted across the globe (employed by 140 of the world’s 193 countries). Corporations under the VAT are not permitted payroll deductions from taxable income, while the proposed plan does permit payroll deductions. This seemingly insignificant detail could have crucial compliance implications with existing World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements, which will be discussed further into the article.

The border adjustment is a component of the broader house proposal.

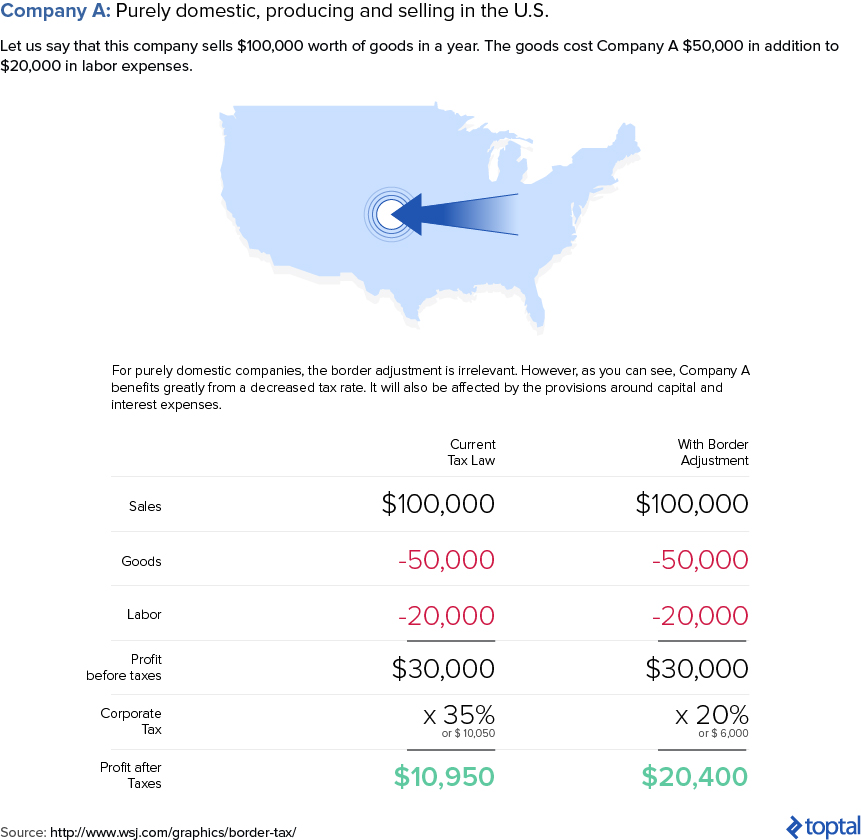

The major components of the House proposal include:

- A border adjustment.

- A decrease in the corporate tax rate from 35% to 20%.

- Interest expenses no longer being deductible.

- Capital investments that may be fully written off or expensed immediately, as opposed to over time (as is currently done).

So it is important to understand that the border adjustment is only an element of the broader House proposal, a point some commentaries tend to confuse.

With the changes outlined above, the new tax system would essentially become a “destination-based cash flow tax” (DBCFT). Here is a breakdown:

- Destination-based pertains to the border adjustment component.

- Cash flow refers to the changes involving interest and depreciation deductibility.

Let us apply the BAT to three hypothetical situations.

One other consideration in this scenario is the potential appreciation in the value of the dollar. According to economic theory, by exempting U.S. exports from taxes, the border adjustment would initially create higher demand for U.S. goods and U.S. dollars. Simultaneously, by taxing imported goods, there would be lower demand for foreign goods and currencies.

Thus, the expected combined result would be a rise in the value of the dollar. Economists are split on whether or not it would occur. However, if the currency rates work as intended, the value of the dollar would appreciate and the cost of purchasing imported goods would decrease.

The BAT aims to raise tax revenue, eliminate incentives to offshore profits, and simplify the current tax code.

Raise tax revenue: In the context of the broader proposal, a border adjustment would generate an estimated $1.1 trillion over the next ten years, which could be used to offset the loss in revenue resulting from the lower corporate tax rate.

Eliminate incentives to move profits offshore: It would eliminate profit-shifting strategies currently utilized by multinational companies such as Apple and its Irish subsidiaries. Since import expenses cannot be deducted from taxable income, it cannot change its domestic tax liability. On the flip side, exports are excluded from taxable income, so tax liability is similarly unaffected. The proposal would eliminate incentives to place intellectual property abroad or load up domestic operations with debt.

Simplify the current tax code: This may seem counterintuitive given the seemingly complicated mechanics of border adjustment taxes. However, the main reason why it would simplify the tax code is because it is easier for corporations to determine where its sales occurred, rather than where the production occurred. According to the Tax Foundation:

It will probably turn out to be much less complicated than the byzantine tax rules that currently govern businesses today. The border adjustment would eliminate the need for firms to comply with our complex rules governing controlled foreign corporations (CFCs), passive foreign income (Subpart F), transfer pricing, interest allocation, foreign tax credits, and accounting for deferred taxes. Under a border adjustment, all companies would need to account for is what items they purchase from abroad and what products they send abroad.

However, the BAT comes with a slew of risks.

WTO violation: While the proposed plan is inspired by the consumption-based VAT, the possibility of it being income-based rather than consumption-based is at the root of much controversy. Consumption taxes do not allow for payroll, interest, or depreciation deductions, as they pertain not to taxable income but to consumption. The House proposal, crucially, includes a provision allowing payroll deductions from taxable income.

Consequently, according to KPMG, it is unclear whether the proposal would replace the current income tax with a consumption tax, or whether it would technically remain an income tax that closely mimics a consumption tax. This distinction has the potential to create inconsistencies with existing World Trade Organization commitments against protectionism. Compliance hinges on whether or not labor costs can be deducted from gross revenue to determine taxable income. If so, the reform would effectively be a corporate income tax with immediate 100% depreciation, disqualifying it as value-added, and would thus be considered a violation.

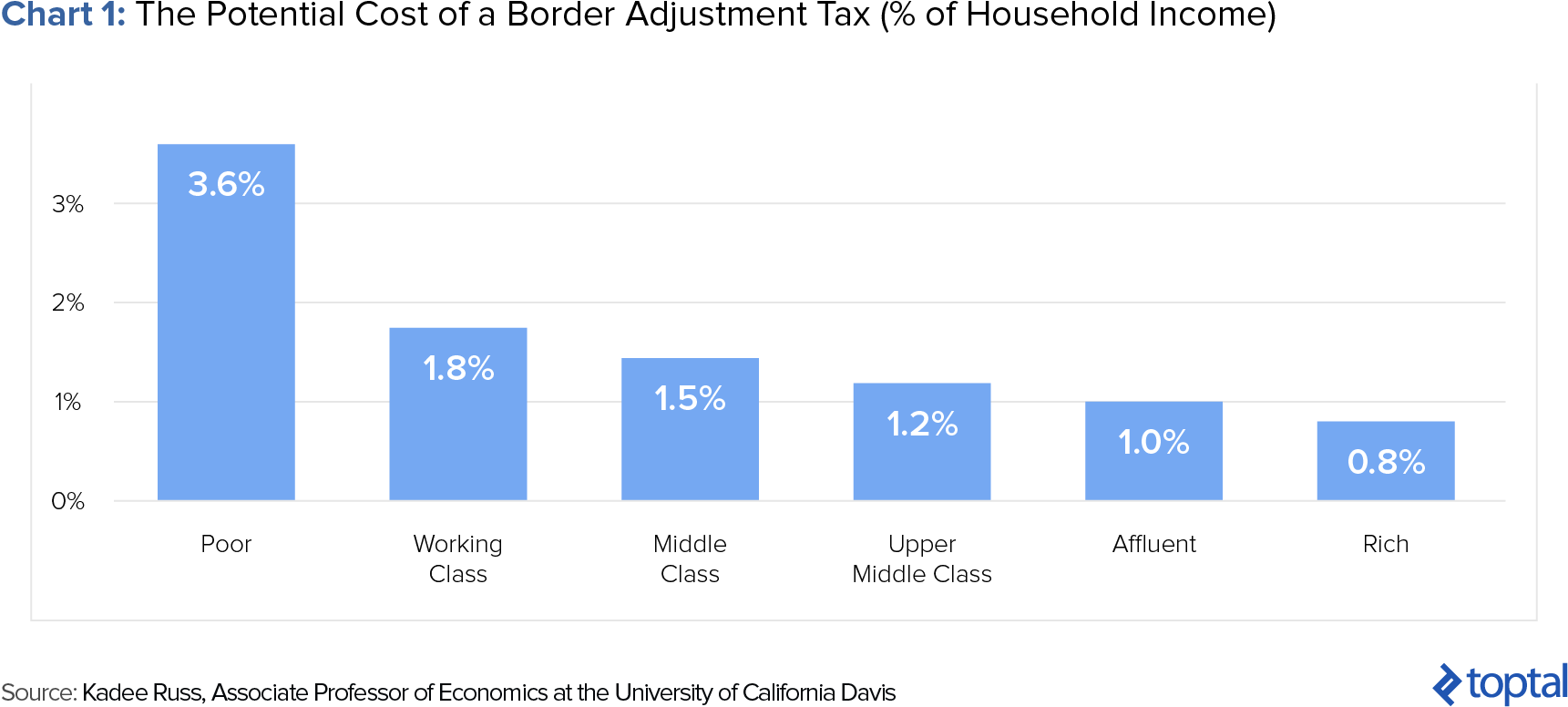

Increased Consumer Prices: Experts are divided as to whether the border adjustment tax would cause increased consumer prices. Some experts argue that businesses would almost certainly pass the cost increases to consumers, who would experience price hikes in imported goods (including everything from foreign cars and gas to avocados and clothing). David French, SVP of government relations at the National Retail Federation, recently commented, “I really hope everybody understands that what they’re really talking about is a 20% tax on the U.S. consumer.”

There is a fear that this cost burden will be particularly difficult for working class and middle class families to shoulder. For example, if the tax includes oil imports, rural Americans will likely be more affected than the more affluent residing in cities.

Others argue that though the 20% import tax might be passed onto customers in the short to medium term, it would concurrently cause an appreciation in the dollar value that would eventually neutralize the additional consumer cost. Harvard economist Martin Feldstein believes that, in accordance with economic theory, the U.S. dollar would appreciate to 125% of its current value—an amount that would more than counter the expected 20% increase in the price of imported consumer goods.

However, this assertion has faced apprehension as skeptics cast doubt around Washington’s ability to accurately predict future foreign currency exchange rates. Skeptics emphasize the sheer number of factors influencing such rates, including federal rate increases, commodity prices, and the overall strength of the U.S. economy.

Foreign retaliation: If the U.S. tries to implement an inconsistent tax regimen, countries could appeal to the WTO and initiate investigations seeking compensation for illegal subsidies received by U.S. exports—ultimately risking a trade war. Opponents point to a risk of retaliation from other countries in response to the change in U.S. policy, potentially drawing $385 billion in tariffs from our trading partners, according to the Peterson Institute for International Economics. The key trigger of this scenario would be if the proposed changes violate existing WTO commitments, something which is still unclear given that the specifics of the proposal remain to be finalized.

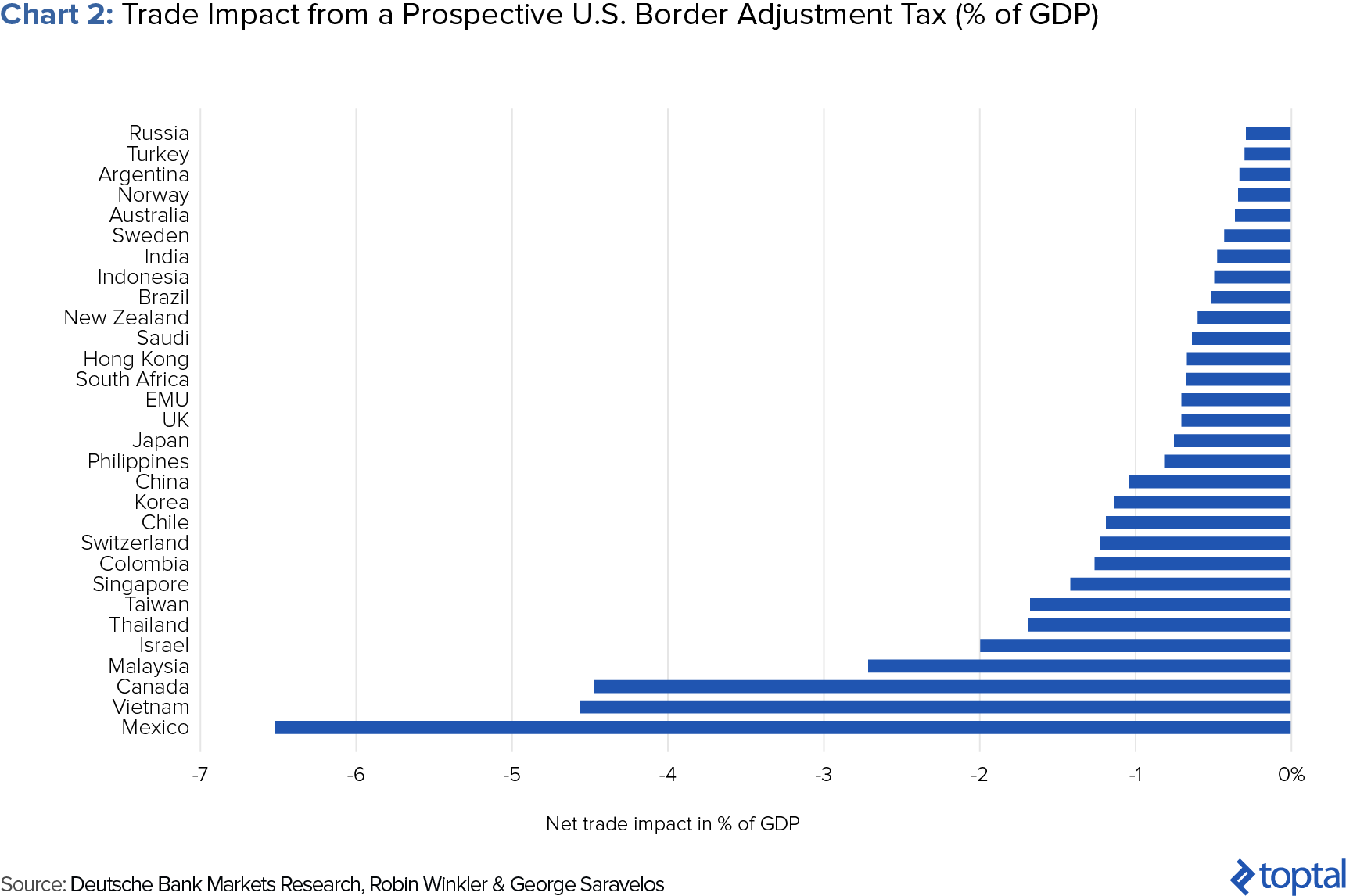

Given the significant effects of the BAT on certain countries (Chart 2), the risk of retaliatory policies is not insignificant should the BAT violate WTO rules. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Deutsche Bank AG economists Robin Winkler and George Saravelos found that Mexico, Canada, and some Asian countries (primarily Thailand and Malaysia) have much to lose should the proposal be implemented, as measured by net trade impact as a percentage of GDP. The fact that Mexico and Canada—two of the U.S.’s largest trading partners—already have the ability to utilize retaliatory tariffs on imports from the U.S. based upon a 2015 settlement by the WTO, makes this threat all the more concerning.

U.S. sectors would be affected at varying levels: Companies are often exposed more heavily on one side of the import/export equation. (e.g., Technology companies that export in high volumes would benefit from the policy, while retailers that import and sell in high volumes would be at a disadvantage). This imbalance would likely be criticized as prejudicial and create sharp divisions among businesses, as they already are.

Companies who are reliant upon imports might not be able to adjust to such an abrupt change: Opponents of the policy have voiced concerns that domestic businesses reliant on imported goods would be harmed by such an abrupt and drastic change. They worry that these companies have long been making strategic decisions and investments assuming a certain set of rules and may be unable to adjust to the shift. Budget retailers heavily reliant upon imported goods are particularly vulnerable to such a change.

American investors would be disadvantaged: If the plan works as intended, then the appreciation of the dollar would hurt Americans who own foreign assets, such as a mutual fund including assets in euros. It is estimated that the loss would be more than $2 trillion.

Though similar to the BAT, the VAT is less controversial.

Border adjustments have historically been popularized and utilized in the context of value-added taxes, a popular taxation system employed across the globe. However, it is a relatively novel concept when applied in the context of corporate income taxation—as is the case with the current U.S. tax reform proposal.

It is important to note that the proposed plan and the VAT are in fact distinct and possess key differences. For one, while the proposed plan is inspired by the consumption-based VAT, consumption taxes typically do not allow for payroll, interest, or depreciation deductions, as they are concerned not with taxable income but with consumption. However, the proposed plan, as mentioned previously, indeed allows for payroll deductions.

In addition, the VAT effectively acts as a sales tax with no competitive impact. According to the EU Taxation and Customs Union, businesses act as VAT collectors while the end consumer actually carries the entire burden of the VAT. Consequently, consumers under the VAT system are comparable to U.S. consumers paying sales taxes on products. In addition, as economist Paul Krugman reinforces throughout his widely-cited paper, the VAT does not create subsidies or trade barriers.

Consider how imports (from the U.S.) and exports (to the U.S.) would be treated by a UK company under the VAT:

Exports: Under the U.S. sales tax system, American companies do not pay sales taxes on purchases made throughout production. However, the UK company pays VAT along the production process but cannot collect it from buyers of goods sold abroad. This is where a rebate is introduced and plays a crucial role: the system allows the UK company to reclaim the VAT already paid out.

Imports: If the UK company imports American goods and sells them, the consumer has to pay the VAT all the same. The UK company then turns this VAT over to the government. Therefore, the U.S. goods are treated in the same manner as the ones produced in the UK. Ultimately, the VAT is neutral.

Let us turn to past instances of high import taxes and foreign retaliation.

Despite a lack of historical examples of border adjustments applied to income taxes, we can learn from past instances of high import taxes and foreign retaliation. As Jeremy Siegel of the University of Pennsylvania warns, “if protectionism does break out globally, it would be disastrous […] if there is a trade war, the market would react extremely negatively […] we’d be down 10% to 15%.”

In the early 2000s, in the biggest case in which the WTO has granted retaliation, the U.S. was found to be unfairly subsidizing exports using certain tax exemptions. As a result of that, in 2003, the WTO permitted the European Union’s (EU) adoption of $4.04 billion in retaliatory tariffs against the U.S. The EU then instituted tariffs on U.S.-based products including everything from leather to nuclear reactors. In response, the U.S. eventually repealed the tax exemption and the tariffs were removed.

In another instance in 2009, a retaliatory tariff imposed by Mexico onto the U.S. regarding cross-border trucking permits reduced the sales of certain U.S. farm products in Mexico by 22% over the course of 18 months, or around $984 million in lost exports. While this number may not seem significant relative to the cumulative annual export amount, it is indicative of other countries’ willingness to take action against perceived injustices, and the significant impact it can have on targeted industries.

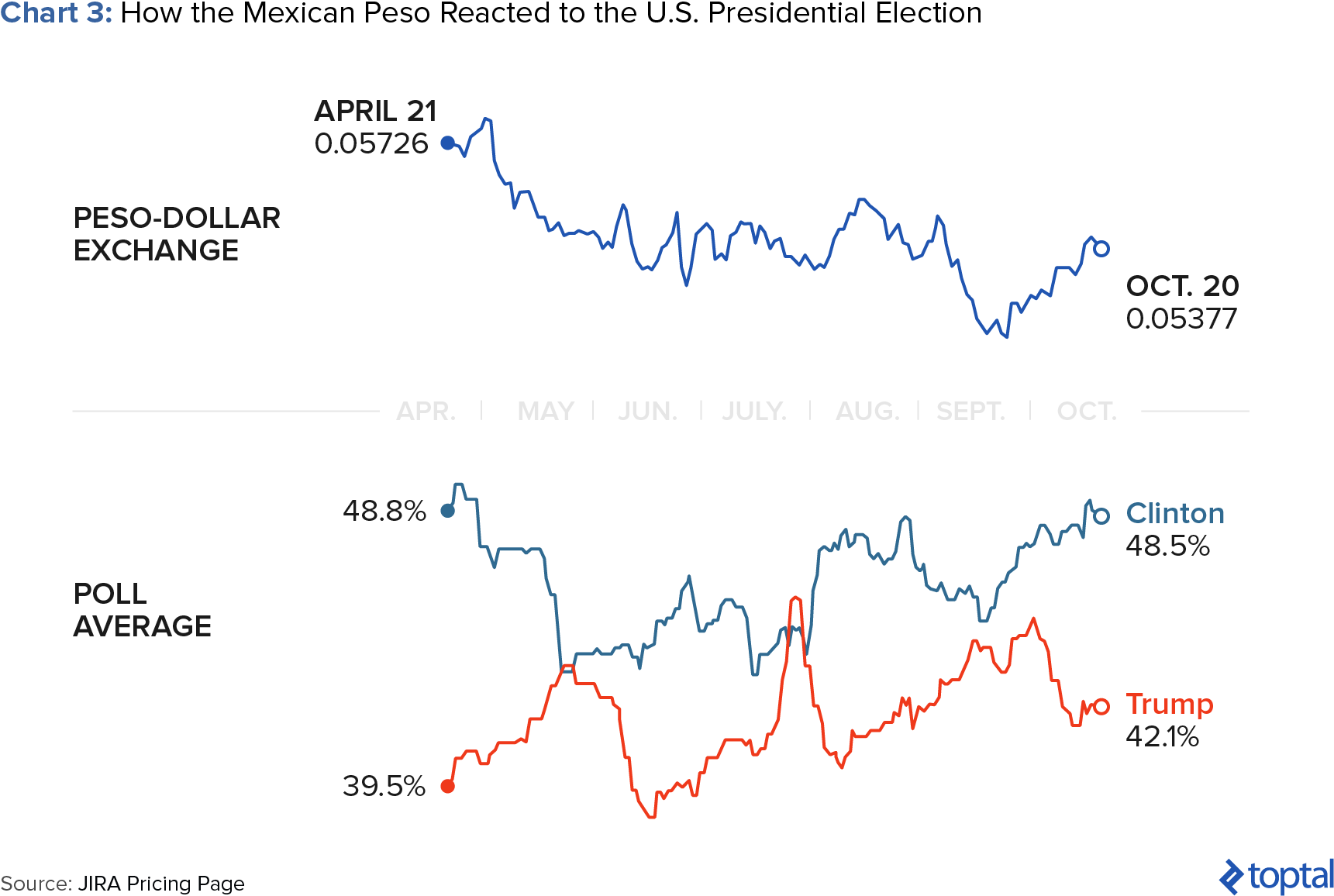

On the other hand, it is also worth noting that currency markets can respond quickly to U.S. policy changes, including the frequent fluctuations in Mexican peso values during the 2016 presidential election. In addition, over 140 countries have a border-adjusted tax as part of their VAT regimes, and there is a vast body of literature related to this which shows showing why currencies would adjust.

However, the Tax Foundation warns that “even if currencies adjust quickly, some factors may slow the speed at which import prices adjust to those changes, including the fact that many goods are priced in dollars internationally.”

Potential alternatives, though imperfect, may yield fewer negative consequences.

A potential alternative to the border adjustment tax would be a smaller straight tax cut. A lower corporate tax rate coupled with looser regulation could add upwards of 10% to corporate earnings, which could cause a ripple of growth across the larger economy.

Another option would be a partial or reduced border adjustment tax, which would maintain the overarching structure of the DBCFT but allow for partial deductions for imports and partial tax exports. Tom Barrack, adviser to President Trump, suggested a border adjustment of 10% instead of 20%. However, this option would add additional complexity to the pure border adjustment model, and might yield negative implications for revenue neutrality.

Alternatively, the U.S. could end the ability for companies to defer taxes on their foreign profits, which would remove the incentive for multinational companies to move their profits into offshore tax havens and raise almost $1 trillion in revenue. This could be paired with an effort to close existing tax loopholes in the tax code, such as requiring companies to pool their foreign tax credits and removing distortive tax expenditures such as accelerated depreciation or domestic manufacturing credit.

Going Forward

It is difficult to predict what will happen regarding the House proposal, especially given the President’s unclear stance on the matter. While some organizations are already positioning themselves in anticipation of its implementation, such as hedge funds increasing their exposure to futures and options linked to WTI (domestic crude oil), others, such as large retailers, are publicly voicing their fierce opposition.

Still, with the combination of the proposed tax reform, Brexit, and the European elections, we may see significant currency exchange volatility in the near future as the system absorbs and adjusts to these changes.

Understanding the basics

What is a border tax adjustment?

A border-adjustment tax conforms to the “destination-based” principle whereby the tax is levied based on where the good is consumed (destination), instead of where it was produced (origin). Put simply, a BAT taxes imports but not exports, creating incentives for companies to import less and export more—a significa

What is a consumption tax?

Consumption taxes do not allow for payroll, interest, or depreciation deductions, as they pertain not to taxable income but to consumption. The House proposal, crucially, included a provision allowing payroll deductions from taxable income. While the proposed plan was inspired by the consumption-based VAT, the pos