How to Understand and Appraise Private Real Estate Fund Investing

The extent of investing in real estate for most individuals is in the bricks and mortar of their own house. For braver investors, there are a range of other options, the most notable being private real estate offerings. Similar to PE and VC funds, these structures can allow for tailored investments in skilled management teams undertaking complex projects.

The extent of investing in real estate for most individuals is in the bricks and mortar of their own house. For braver investors, there are a range of other options, the most notable being private real estate offerings. Similar to PE and VC funds, these structures can allow for tailored investments in skilled management teams undertaking complex projects.

Martin is an seasoned real estate and PE executive that has completed over $200m of projects and advised a range of Fortune 500 companies.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT

Executive Summary

There Are Many Different Forms of Private Real Estate Investing

- Real estate exposure can be gained through a variety of instruments. Public stocks, real estate investment trusts (REITS), direct ownership, and private real estate investment funds are the main types.

- Private real estate funds offer an investor more choice with which to choose a manager and investment theme that fits into their risk and exposure profiles.

- One core advantage of private real estate investments, over more passive instruments like REITs, is the ability of the investor to have meaningful influence with a sponsor about investment strategy.

What Are the Main Considerations to Take When Assessing a Potential Real Estate Fund?

- The actual investment being made should be the first consideration to mull over for a private real estate deal. Assess whether the underlying bricks and mortar make for a compelling project and whether the prevailing macroeconomic headwinds are in its favor.

- Return on cost (ROC) is a simple, yet effective barometer for assessing the yield projections of the performance and gaining a top-down view of the costs and incomes associated with the project.

- The sponsor's strategy needs to be dissected in relation to any difference between the ROC projections and fund IRR target. Is the plan to finance the properties at a lower rate? Is it to sell the properties at a premium? Compare the sponsor's macro view with your own and its prior experience to actually undertake what it is promising.

- The legal wording of the fund agreement will show how much leeway the sponsor has within its undertakings. For a single construction project, this will be relatively rudimentary, but for portfolio funds, the looser the legal wordings, the more the end result could differ from expectations.

Pay Attention to the Compensation Elements and Downside Risks

- Unlike other private investment funds, such as venture capital and private equity, the fee and carried interest components of real estate funds do not tend to follow a standard convention.

- Fees are positively correlated with to the effort needed on the sponsor's behalf to execute the investment. Thus, for a building project with hands-on management required, expect a higher compensation element over a passive buy-and-hold fund.

- Lean on experts to help you assess the sponsor, the terms, and the underlying investment. It can also help to draw up a comprehensive list of fatal flaw risks that could undermine the project (e.g., environmental issues or policy changes).

In a market environment where it has become increasingly difficult to earn high quality returns in stock and bond markets, many are turning to alternative investments. The promise of alternatives is to improve portfolio yields and to provide investors unique, untapped opportunities to invest in less efficient markets; at the same time, these investments pose a new set of challenges and issues for investors.

While there are a variety of alternative investments available, one of the most important options in the alternatives space is private real estate offerings, whether one is talking about investing in funds or a specific property. This article will introduce the benefits and challenges of investing in private real estate offerings and share some tips for evaluating these investments.

But before we jump in, a quick programming note. Two of the most common means of investing in real estate—real estate investment trusts (REITs) and direct ownership of real estate—will not be covered here and will be the topic of a future article. This article will focus on investments that are smaller and more targeted than the typical REIT, but less involved and time intensive than direct ownership. That is, investing in a private equity real estate fund or project managed by a professional, third-party investment manager.

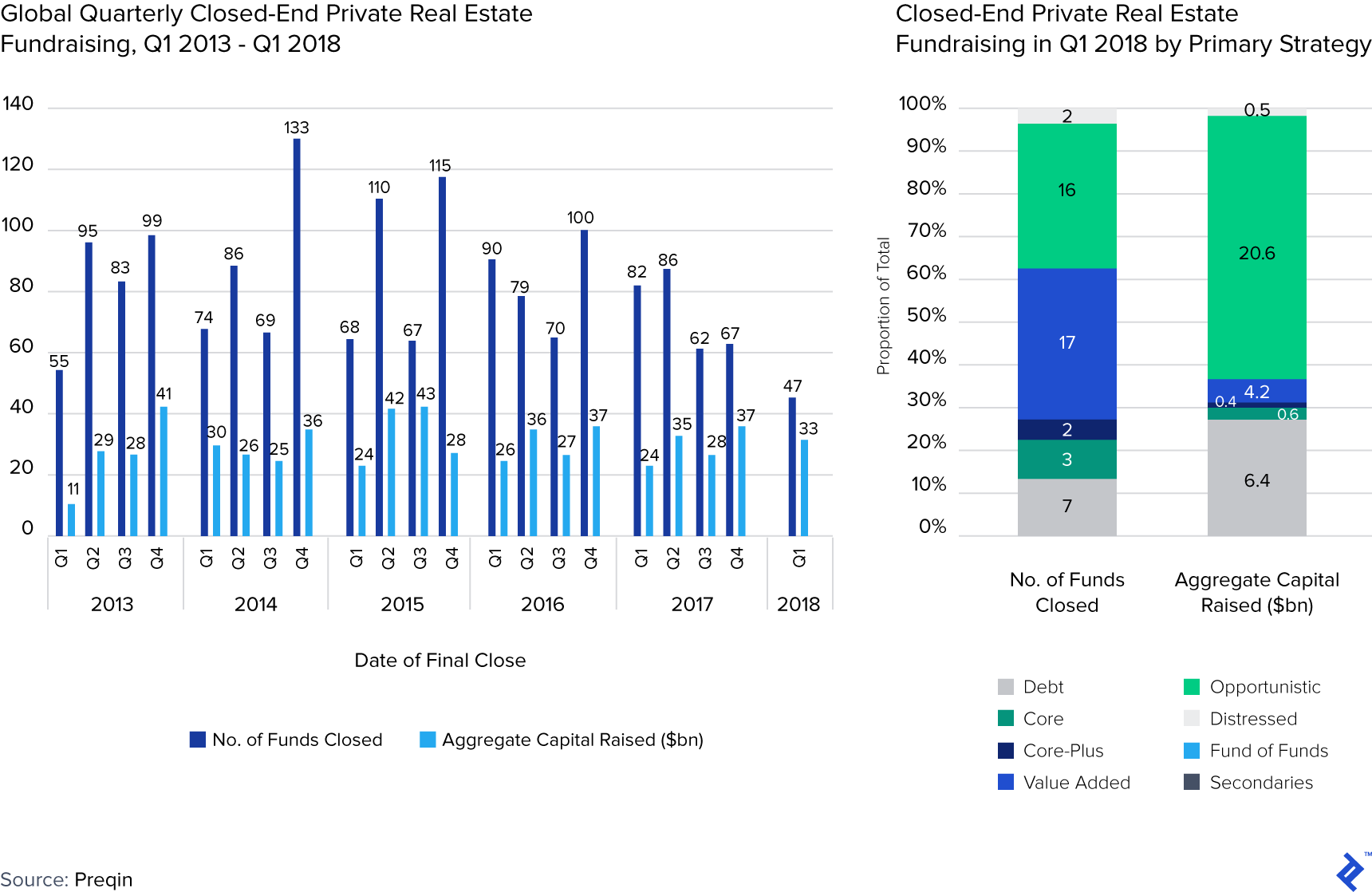

In recent years, private equity real estate funds have been raising money at consistent levels between the $20-40 billion range per quarter according to Preqin. There are several different investment themes deployed that scale through certain risk profiles: from “core” (safe, trophy properties) to “opportunistic” (highly leveraged investments, with little to no cash flows). Incidentally, opportunistic funds are the most popular choice for investors right now, in terms of funds closed and aggregate capital raised.

Investments in Private Real Estate Fund Offerings

For many private real estate investors, the best option is to invest in assets being acquired and managed by a third-party, professional investment manager (called a “sponsor”). This can be in the form of a fund, for a single, specific investment, or a hybrid structure that combines existing assets with future acquisitions. Here is how these real estate funds work:

- The investor benefits from the experience of the sponsor, whose full-time focus is typically real estate investing, and who often has established operations run by a team of professionals.

- The cost of investing is typically known up front, and spelled out in contract in terms of manager fees, carried interest and other benefits.

- Investments can be made in a variety of asset types and sizes, and effective diversification is possible even for a smaller investor; investors can also make investments in structured products like senior loans, mezzanine debt, preferred equity or LP equity, each of which usually required specialized expertise and relationships, and can be difficult to invest in on a one-off basis.

- Depending on the scale of the investor’s investment relative to the overall fund or project, the investor may have the opportunity for meaningful input on decisions with respect to acquisitions, management, financing, and disposition of assets.

- At the same time, day-to-day management is typically a duty of the sponsor, and does not become a distraction to an investor’s other activities. This is especially important for a diversified manager, who may have more pressing responsibilities beyond operational management of real estate.

The benefits above are valuable; however, there are also issues to consider when making investments in private real estate offerings. And while most managers will provide a great deal of information to investors evaluating their opportunity (and in fact are required to do so by law in many cases), reviewing that information and using it to come to a clear basis for a decision to invest, or not, remains in the hands of the investor.

Investing Effectively in Private Real Estate Offerings

There are many types of real estate funds, with a variety of strategies, goals, and structures. A private investor must become good at understanding and assessing the specifics of each offering to be effective. This section will help you to start considering how this type of investment might fit in your portfolio, and the key areas to consider as you are evaluating new opportunities.

The Underlying Investment Itself

Warren Buffett has a great saying: “When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.” The same is true in the real estate industry, and therefore often the first and most important question to be asked about a new opportunity, is what exactly the investment is and why it is worthwhile to make it. The real estate industry is one of the most diverse asset classes available to investors, and it is full of niche strategies and businesses that fit a specific purpose, and offer a certain return. One of the exciting things about real estate is that you can find investments as conservative as low leverage loans on urban trophy assets which have a profile similar to investments in high-credit bonds, all the way to highly speculative development projects that can have returns more like a VC fund or small cap equity investment. And everything in between.

While going through each opportunity available in the marketplace is far too broad a topic to be covered here, it’s worth keeping in mind that this enormous variety exists. And it is useful to think about how to frame a set of questions that can surface the “what” of a potential investment. Where does it fit in the spectrum of opportunities?

Start with the ROC

Often, a good starting point is to have the sponsor provide their own assumptions and pro-forma financial forecasts regarding the investment or fund. A high-quality sponsor will have their pro-forma financials prepared for review and will be able to answer detailed questions about their strategy, assumptions, and results, and to explain how and why the structure they are building works. While this may seem obvious, there are countless investors who will make investments without this information, based on a desire for exposure to a manager or asset class, and without a detailed explanation of the business.

Once you have the financials, a detailed review should allow you to develop a set of questions to further assess the opportunity. There are countless approaches to evaluating pro forma financials, and evaluating a business model, and too many to cover in detail here. But I will mention one particularly useful one in real estate here—the Return on Cost (ROC).

I define ROC as what you get if you divide a property’s stabilized income (net operating income) by its total all-in cost, including the cost of buying it, improving it, developing it, leasing it, financing it, and so forth (including all fees). Here is the formula:

Return on Cost = ([Gross Potential Rent] - [Vacancy and Bad Debts Expense] - [Operating Expenses]) / ([Property and Project Costs] + [Project Related Fees and Costs] + [Other Costs])

Let’s take a simple example: You buy a piece of land for $700,000 and invest $300,000 to develop it and rent it to a tenant that pays $70,000 of rent and covers all of the operating costs. Your ROC is then 7.0% = $70,000 / ($700,000 + $300,000). An easy way to think about this number is as the expected yield of the property at the moment that it is stable.

Uncover the True Strategy

The reason the return on cost is so useful is that it gives you a baseline for asking questions. If the planned ROC for properties to be acquired in a fund is 7.0%, but the fund manager is promising a 12.0% return to investors, then obviously there is a disconnect. And the question that may be asked is what that difference is—is the plan to finance the properties at a lower rate? Is it to sell the properties at a premium? Is it that the manager expects the market rents to grow over time? A combination of those things? something else?

The answer to that question (what is the disconnect?) will usually tell you what the “real” strategy of the manager is, and what the inherent risk they are asking you to take is. Knowing the strategy, in turn, will help you make a more informed decision about the investment—for example, if the disconnect is future growth in rents, do you believe that thesis? If it’s a sale of the property at a premium in a few years, is there evidence that it can be sold at the proposed price? And so forth.

Do the Legal Terms Line Up with the Strategy?

In addition to developing an understanding of the investment strategy, it is important (especially for investments in funds) to understand the contractual obligations of the sponsor with respect to the strategy. In many cases, a sponsor may have a specific business plan that is shared with investors, but a broader set of options when it comes to the legal requirements set by their fund operating agreement. Some flexibility will be warranted, but if you’re not careful, you may end up with a set of investments that are very different from what was originally intended. At a minimum, it’s important to understand what flexibility a sponsor may have, and it’s usually wise to have in mind some sense of the flexibility you are willing to provide given the quality of the sponsor.

Obviously, this element is simpler when the opportunity is a specific property (rather than a fund), but even there, it is important to understand what options are legally available to the fund or sponsor as all investments evolve over time.

Sponsorship Issues

When making an investment in a private real estate offering (and especially when considering a fund), the most important component outside of the investment itself is the sponsorship. To a great extent, the service you are “buying” when investing in a private offering is the sponsor’s experience, know-how, relationships and trustworthiness. Evaluating these elements up front is key to investing successfully. That person or organization will be responsible for making the right decisions with your capital in terms of which investments to acquire, what management decisions to make, and how to treat you as an investor.

This element is often the trickiest part of underwriting private offerings. It stands in contrast to evaluating the investment itself, where most of the considerations are based on facts, evidence, and numbers. Choosing a great sponsor is mostly a qualitative exercise.

Many groups have tried, with mixed results, to “quant up” the sponsor evaluation process with a careful review of track records, background checks, lengthy questionnaires, and reliance on a variety of quasi-scientific indicators.

Others have set themselves broad rules to manage this issue, ranging from not investing with anyone that wasn’t referred personally to investing smaller at first and then in larger amounts when the initial investment has proven successful, and a whole variety of more idiosyncratic decision rules and evaluation methods.

While these approaches often have some common-sense appeal, I have not seen either fully pay off in the way they are intended to in terms of assuring an investor’s returns. The challenge is that after the reviews are done and the reports filed, at the end of the day, investors will typically find themselves back in the same place where they started—having to make a qualitative decision about whether they trust a person or group of managers to carry out the proposed investment program successfully.

Unfortunately, there is no silver bullet for making this judgment call, but there are three useful strategies to consider in making the evaluation.

Look for the Story, Not the Score

First, in completing the evaluation of the sponsor, try to build a story rather than a score. The goal is to understand what experiences that person has had, what those experiences say about them, and how that narrative will grow into the future. It’s often hard and time consuming to learn someone’s story, (which in part is why there is such reliance on stylized facts and track records), but doing so will put you in the best position to understand what might happen next, and how that person may react under different circumstances.

Skill and Resource Match

A second strategy is to focus closely on what skills are needed for the investment to be successful, and how the manager brings those specific elements to the table. If the investment thesis relies on a sponsor’s ability to build a building, do they have that skill? Or have they hired it out to a competent group? If a fund’s success requires high-level statistical analysis, does the sponsor have knowledge of that area? What is the core set of skills the sponsor is bringing to the table, and are they a good fit for the investments being made? Is the puzzle complete, or is there a jarring hole in the middle? Too often, investors focus on broad generalizations that may not be relevant in the current situation. A sponsor may have been hugely successful managing a portfolio of existing apartment buildings, but are those skills now going to be applicable when they are acquiring retail land to build shopping centers? Or investing in industrial value-add projects? Or anything else?

Closely related to what skills are needed is what other resources are needed. For example, if the sponsor is required to sign on loans, do they have the capacity to do so? If they may be required to put cash in each transaction, do they have the cash (or at least a means of getting it)? If the investments require a team of professionals to operate, is that team in place?

Incentive Alignment

Finally, it’s important to evaluate a sponsor’s incentives (and don’t forget the non-financial ones). Incentives will not wholly determine the sponsor’s choices, but they certainly have an important vote. Financial incentives can vary substantially based on the investment structure proposed, and the sponsor’s overall business. Non-financial incentives will vary based on the sponsor’s business, their priorities, and the circumstances they face. They will also be broadly influenced by the sponsor’s personality, character, and history. The next section will focus on financial incentives.

Sponsor Compensation in Private Real Estate Investing

Fees and Carried Interest

With the advent of low cost ETFs and the broad success of modern investment management ideas, it’s hard to have a discussion about any investment these days without a discussion of fees and carried interest. This is a difficult topic when it comes to real estate investments, as the industry remains somewhat of a Wild West with respect to how sponsors are paid. Most other investment classes have, if not perfect adherence to a standard, at least a basic established orthodoxy about what should be charged and how things should be structured. Not so in real estate funds.

The driving factor behind this is that, first, a real estate investment fund requires varying levels of management time and effort, and, second, are highly structured and capital intensive—and therefore have a wide variety of potential capital options and alternatives that are considered when an investment is made by a sponsor (of which raising money through a private offering is only one).

Based on the above, for example, a fairly large fee may be entirely appropriate for a development project that requires a sponsor to hire full-time staff to manage and focus on the project, or for a specialized debt investment that requires a large amount of business development time to identify and negotiate new opportunities. Those same fees may be wholly inappropriate for a long-term buy-and-hold fund that is doing nothing more than acquiring properties and sitting on them.

Alternate options available to the sponsor will also influence what the right economics are. For example, while an investor may prefer to have a low carried interest in a fund, if the sponsor is able to complete its transactions competitively using high-yield debt (or another alternative), it may not be possible to negotiate the investor’s desired pricing no matter what may be perceived as fair.

What’s important in real estate is to develop an understanding on each transaction of the elements of risk and effort being undertaken by each party, and the level of return under discussion, and to try to come to an arrangement where those things are aligned. If they are then the structure is likely appropriate, but if not then the investor should think carefully about their reasons for making the investment.

Issues Related to Specific Terms

There are a variety of terms related to private real estate investments that are important to consider. A partial set is included here but not covered in depth. Often, an investor’s advisors and attorney will be well-positioned to evaluate these items for a specific investment, and provide guidance on what is typical and reasonable. At a minimum, it is advisable to know the terms for each of these items in a proposed investment so that the decision to invest can be made with a complete picture.

- Discretion/Authority – To what degree does the investor have the right to become involved in evaluating a potential transaction, under what circumstances, and in what way?

- Liquidity/Disbursements – When will the investor receive their initial investment back? What is the means by which repayment will be made? What happens if repayment doesn’t occur according to plan?

- Funding Conditions – How are investor funds made available to the fund/company? Under what schedule and with what kinds of controls?

- Additional Funding – What happens if additional funds are required that were not planned for?

- Treatment of Investor Funds – Do investor funds receive preferential treatment to other funds? In what ways?

- Investor‘s Return – How are returns to the investor calculated? How are they split with the sponsor?

- Other Financing – Can the sponsor/investment company secure financing in addition to the investor’s capital? Under what terms and at what times?

- Other Requirements of Investors – Does the investor have to provide anything related to the transaction other than their capital? Most importantly, are there any agreements that investors have to sign or provide security for?

- Default – What happens if either the investor or sponsor fail to meet their obligations? What are the remedies? What is the process?

- Other Costs – Are there costs of investing outside of those charged by the sponsor?

- Reporting – What reporting is required to be provided to investors, and what happens if it is not provided?

Of course, this is only a partial list, and there are a variety of issues that will be specific to certain types of investments, sponsors, or structures. Ultimately, it’s the holistic view of the investment that needs to make sense.

Putting It All Together

While the sections thus far lay out the main issues to consider in making an investment in a private real estate offering, no investment will check all of the boxes. In some ways, this is by design. There is a market for these types of investments, and the price that an investor can charge for their capital is often inversely related to the demand for the investment in the marketplace. For example, a very experienced sponsor investing in an in-demand sector will often demand sponsor friendly fees, carried interest, and terms, and may limit the degree to which investors are able to exert control after committing to invest. Alternately, a new manager may provide a better set of terms and investor rights and lots of direct access but may not have the same type of track record or may operate in a less well-known sector.

Because of this balance, having the full picture of an investment opportunity and a complete evaluation prior to a decision to (or not to) invest is important. One tool that can be useful to investors is a scorecard document that allows the evaluation of each element of an opportunity in isolation, and then the chance to view and think about the investment as a whole rather than focusing on its component parts.

This is useful because, too often, investors fall into the trap of missing good investments because of one, or two issues get too much attention relative to the complete picture, or conversely, missing the warning signs on a bad investment because of one overwhelming positive factor. A good investment process is one that emphasizes a data collection period where decisions aren’t being made and culminates in a decision-making period that is completed when a more complete picture is available. This allows for opportunities, and their issues to be put in proper perspective.

But Watch Out for Fatal Flaws

While the holistic view tends to be the best place to make decisions, it’s important to keep an eye out for fatal flaws in a potential investment. These are issues which in and of themselves change the entire outlook for an investment.

A perfect example in real estate development is a project which has excellent economics, experienced sponsorship, great deal terms, and excellent location and tenancy, but also happens to be located on a contaminated property.

It’s not appropriate to score the environmental issue in one section of a review and say that the positives outweigh the negatives—this is an issue that needs to be thoroughly understood and in and of itself can (and should) be able to remove an opportunity from the consideration set.

This is just an example, but the point broadly is that a scorecard can help maintain perspective, but shouldn’t outweigh further judgment if there are issues that compromise the investment in and of themselves.

Conclusion

There are a great many opportunities available for private real estate investors to put capital to work, and private offerings can be a great source of interesting investments that can augment an investor’s portfolio.

At the same time, these investments require care on the part of the investor. Hopefully, this summary will put you on the right track to explore the investment class and will get you started on building your program or portfolio.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- Complex but Integral: An Overview of Real Estate Waterfalls

- Considerations for Raising Your Own Private Equity Fund

- The Wealth of Nations: Investment Strategies of Sovereign Wealth Funds

- Real Estate Financial Modeling: 3 Costly Mistakes to Avoid

- The Most Exciting Asset Class in Private Equity? Search Funds From the Investor’s Perspective

Understanding the basics

What is a real estate investment fund?

Funds that invest in underlying assets that are property, either on a residential or commercial basis. Activity can range from constructing new property or managing existing properties. Returns are gained from income generated by the property and appreciation in asset values

What is private real estate?

Private real estate investing is when a third-party sponsor manages investments in real estate assets. The sponsor will be paid a fee and will have incentives for generating a return for the underlying investors.

Martin Kemeny

San Francisco, CA, United States

February 10, 2017

About the author

Martin is an seasoned real estate and PE executive that has completed over $200m of projects and advised a range of Fortune 500 companies.

Expertise

PREVIOUSLY AT